The UK’s media landscape feels as unstable now as it has been in a very long time.

The BBC recently cut its existing news budget by 4%, axing 130 jobs and cancelling HARDtalk, BBC Click, and BBC Asian Network’s bespoke news service (among others).

The Guardian is in talks to sell The Observer to Tortoise Media, while The Daily Telegraph is in talks for its own sale to US website The New York Sun.

Traffic from Facebook and Google to media outlets has fallen off a cliff, while TXitter’s influence as a breaking news service slowly wanes. And all these changes are happening while genAI looms over the landscape at large.

Of course, much of this instability comes from the long-term squeeze on the economics of media, and the reality that making money from news is incredibly tricky. However, the shifting landscape also reflects changes in the population’s media consumption habits, with outlets again being forced to rethink their publishing approach in response.

Changing consumption habits

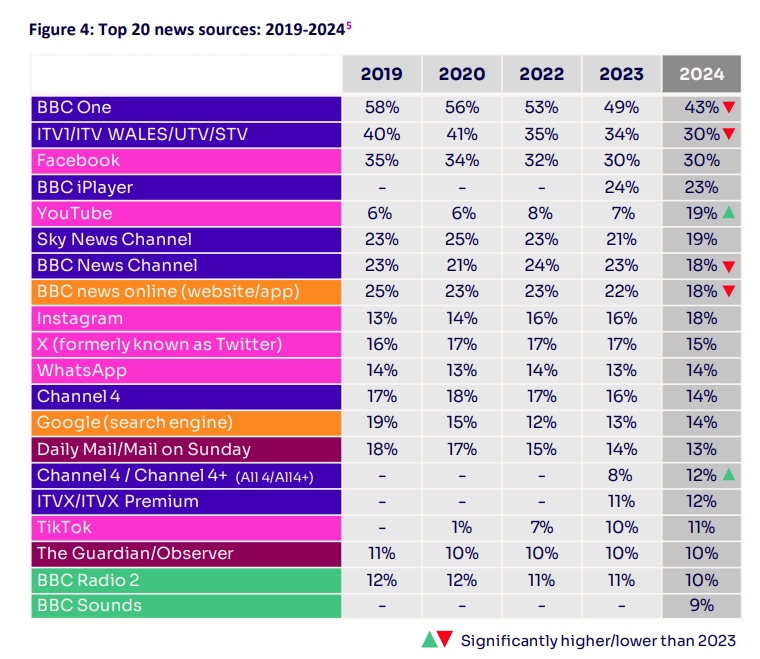

Most notably, we reached a tipping point recently, with Ofcom reporting that as many people now get their news online (71%) as they do from broadcast (70%). BBC One remains the single largest news source for people in the UK, showing the enduring power of broadcast for reach. But the reach of BBC One’s nightly news is on the slide, with only 43% of adults now claiming to watch it (down from 58% in 2019).

The past 12 months have also seen significant growth in video-led tech platforms contributing to people’s news diets. 11% of people in the UK now use TikTok for news, while the use of YouTube for news has more than doubled in same time period. 19% of people now use YouTube for news, making it the second biggest online platform after Facebook (30%).

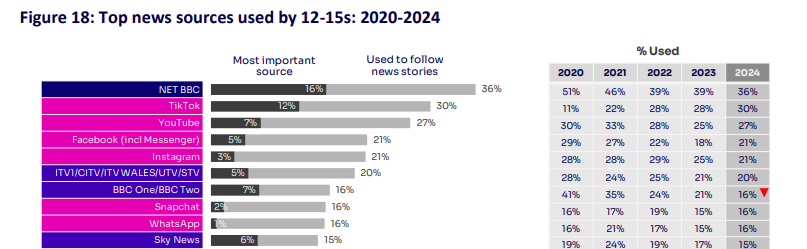

That preference for news delivered via short-form video is even more prevalent among teenagers in the UK. Thirty per cent of 12-15 year-olds get their news from TikTok, with 12% of them considering it their most important source.

But we need a more in-depth look into that data before anyone starts predicting a “pivot to video” like it’s 2015 all over again. In particular, we must unpack what “news” means in this context.

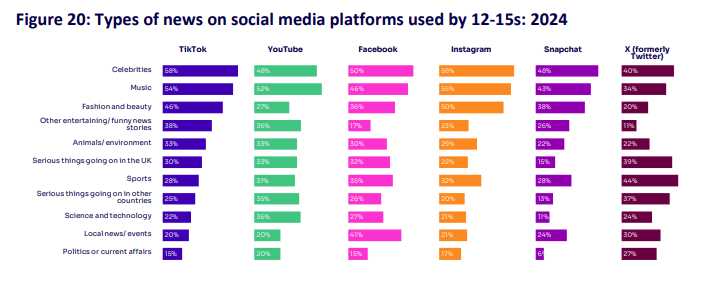

That’s because the news those teenagers consume on TikTok and YouTube isn’t necessarily what we think of news when we’re coming up with campaign and story ideas.

What counts as news?

The top topics teenagers enjoy are celebrities, music, fashion and beauty and “entertaining/funny news stories”. You must scan down to the sixth most popular topic to find “serious things” on the list, with local news and politics languishing at the bottom.

It’s also the case that anyone using social media platforms to access news (not just teenagers) is most likely to discover stories via the trending topics of that platform. Only a tiny proportion of teenagers (7% on TikTok) follow a traditional news organisation. Consuming news via short-form video is a very different experience from tuning into the nightly BBC One news.

And finally, zooming out to the broader population, only 43% of people who use social media and online sources for news felt they “provided trustworthy stories”, compared to 69% of people who use TV for news. This sense of distrust in news viewed online was even more acute among younger people – only 37% of 16-24 year-olds trust the stories they see in their feeds.

Taken together, these data points around media consumption habits speak to a tension within people’s relationship with the news.

They want to feel informed about current events to maintain their innate human connection to the world. But there’s a growing sense that the media and information ecosystem is ill-equipped to cater to different audiences’ needs when it comes to news.

A question of trust

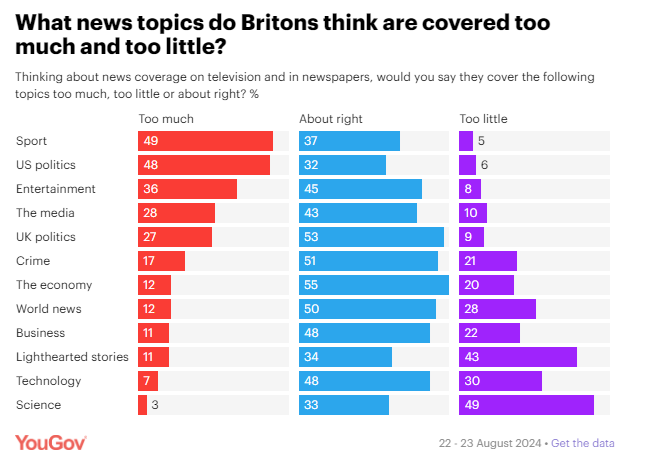

People want news from their social feeds but either distrust what they see or feel the stories are irrelevant to their interests. A recent YouGov survey found respondents want less US politics and more “light-hearted stories” and science coverage in their lives.

TV news remains the closest thing to a trusted news source, particularly the BBC One nightly news bulletin. However, a linear nightly news bulletin is ill-equipped to cater for modern media habits.

The available research points to a growing expectation gap between what people want from their news and what they receive. And it’s clear that this expectation gap plays a significant part in the increased turbulence within the news media industry.

People want to receive their news on the platforms they use the most, and they want the convenience of having that information curated for them (most commonly by algorithms). However, at the same time, they can also feel bombarded by the volume of news in their feeds and overwhelmed by stories that feel depressing or irrelevant.

Young people especially distrust what they see in their feeds, feeling that it lacks the rigour of the more traditional news sources that they’re aware of but don’t engage with. There is also a generational divide around the very concept of news itself. Younger people see news as synonymous with entertainment; for older people, news remains harder-edged and more political.

Know your audience

These tensions and divides in our news consumption habits point to a media ecosystem whose cracks and instabilities are becoming more stark every year.

It may be that these fractures and fissures only exist when we try to study “news” in totality, as one singular concept. Any form of news, from the earliest newspapers to the latest generation of short-form video newshounds, is multifaceted. There’s always an element of human curation based on your interests. You choose the section of the paper you flick to or which videos to watch in your feed.

That means if we start all our campaign planning and story generation with specific target audiences in mind, we may be able to deftly circumnavigate the tricky relationship “people” have with “news”. We can take advantage of the rise in younger people using short-form vertical video for news by being granular in who we want to target (young people is an awfully vague term) and understanding precisely what it is those audiences look for in their feeds that relates to their notion of news.

In fact, no matter how the future of news and our media ecosystem plays out, brands and businesses must prepare to reflect the current fragmented landscape in campaign planning and idea generation.

That means having a clear and detailed understanding of your target audience and their media consumption habits.

That means thinking about how to make those campaigns and stories work across various channels.

It also means having a plan to measure the impact of those campaigns and stories over time so that you can continue to iterate and improve.

And while there is a swirl of instability and uncertainty currently engulfing news media as a whole, plenty of factors remain the same as they ever were. Your story needs to be interesting and actually contain some news to have a chance of being covered. Relationships with journalists remain essential to securing that coverage. And the media still has the power to influence debate and encourage people to think differently about specific topics (or to think about them at all).

Although the future of news may be tricky to predict, the fundamentals seem likely to remain the same.

Read more Insights & News