Reform leaning voters open to the idea of a broad deal with the EU

International negotiations and the potential for economic turmoil continue in response to President Trump’s ever evolving tariffs pronouncements.

The UK government has a series of tough choices to make, from what to give away to get trade deals with the world’s major trading blocs, to how to respond fiscally to the prospect of a tariffs-induced contraction.

Domestic political considerations are far from the only variable that matters to those calculations, but they will inevitably play an important role.

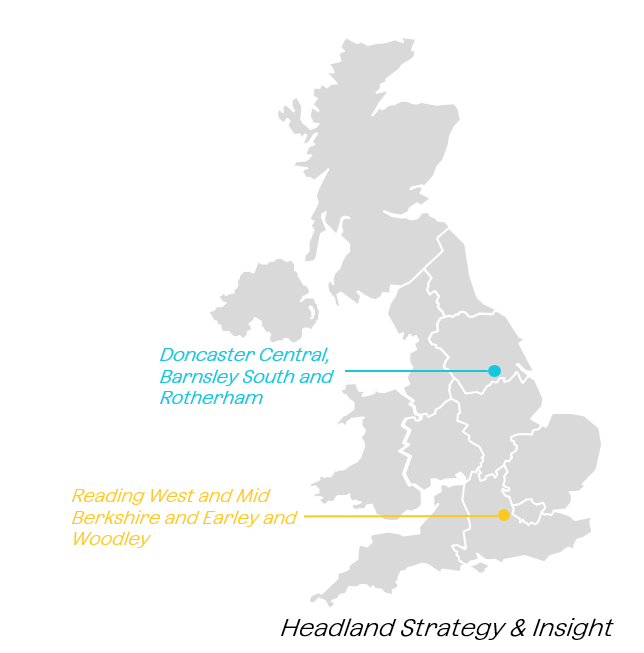

To that end, last week Headland initiated and moderated a pair of focus groups with two types of Labour’s 2024 voters: those who would now plan to vote Reform, and those who would now plan to vote LibDem (or Green). They were held online, with voters living in marginal constituencies where those parties are a threat to Labour holding the seat.

Political parties regularly use focus groups to test their narrative, explore the language of their messaging, and most fundamentally to understand the amount of political space they have to manoeuvre. The Labour Party uses them extensively – on secondment in 2024, I was part of a team that conducted multiple focus groups daily during the General Election campaign.

At Headland we use them the same way: to understand the way in which target audiences – citizens, consumers, employees and more – are likely to respond to corporate and political messaging. How much space does a company have to do X or say Y?

So what do Labour’s target voters think? How much space do Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have to respond to Trump’s tariffs?

Trade deals

First, on trade itself. The most important finding was the latitude that Reform-minded voters give the government to do a deal with the EU. There was an acknowledgement of the vital importance of trade with the EU – more so given the behaviour from the US – and a more general feeling of regret from many at their vote in the 2016 Brexit Referendum.

There was no feeling that doing a deal with the EU would constitute a “betrayal” of the Referendum. Even on issues that are seen in Westminster as politically contentious, such as allowing young Europeans to live and work in the UK (the Youth Mobility deal), there was acceptance.

As one Reform-minded voter, a plumber from Doncaster, put it:

“Geographically, Europe is our strongest trading partner. We do have to align with them, even if we don’t want to be part of it.”

The potential political costs of a deal with the US look somewhat higher. Of the various concessions to the US that have been touted in the media over the last few weeks, few would be tolerated by Labour’s target voters.

Those that are most acceptable include reducing our tariffs on imported US cars (a logical concession in a negotiation) and abolishing or reducing the Digital Services Tax (not something of which voters are particularly aware).

But some of the more totemic options, for example changing food standards, got a vociferous response. It is small wonder the government has clearly ruled out allowing chlorinated chicken to be imported. A LibDem-leaning IT manager from the suburbs of Reading summed up the reaction:

“So we’d have to rewrite the rules completely if we were to agree to this, ‘We’ll take your bleached chicken in exchange for less imports.’ I don’t think it can ever fly.”

Fiscal options

The Chancellor has very little flexibility available to her when it comes to the fiscal choices. In the likely political response and Labour’s own commitments, she is bound by her fiscal rules, the promises to not raise the major taxes, and the difficulty of cutting public spending.

Among a set of bad options, it appears from the groups that raising taxes would be the least painful choice. If the economic picture visibly worsens as a result of tariffs, then both types of voters would grudgingly tolerate an increase in taxes to boost health and defence spending.

LibDem leaners were more likely to accept this as necessary:

“The pot is already empty. If we all have to pay a little bit more in National Insurance to right the wrongs, then so be it.”

Inherent uncertainty

Trump’s imposition of tariffs appears to voters to be wildly unpredictable, and their impact uncertain. Unlike the shift in the defence and security situation, the economic threat to the UK and the need for a decisive government response is less clear to voters.

Until an economic contraction becomes apparent and until the government can create a narrative linking that to tariffs, voters are unlikely to accept broken promises or a radical change in policy.

In that context, businesses’ hopes (or fears) of a transformational policy shift in the aftermath of ‘Liberation Day’ are unlikely to be realised.

Read more Insights & News